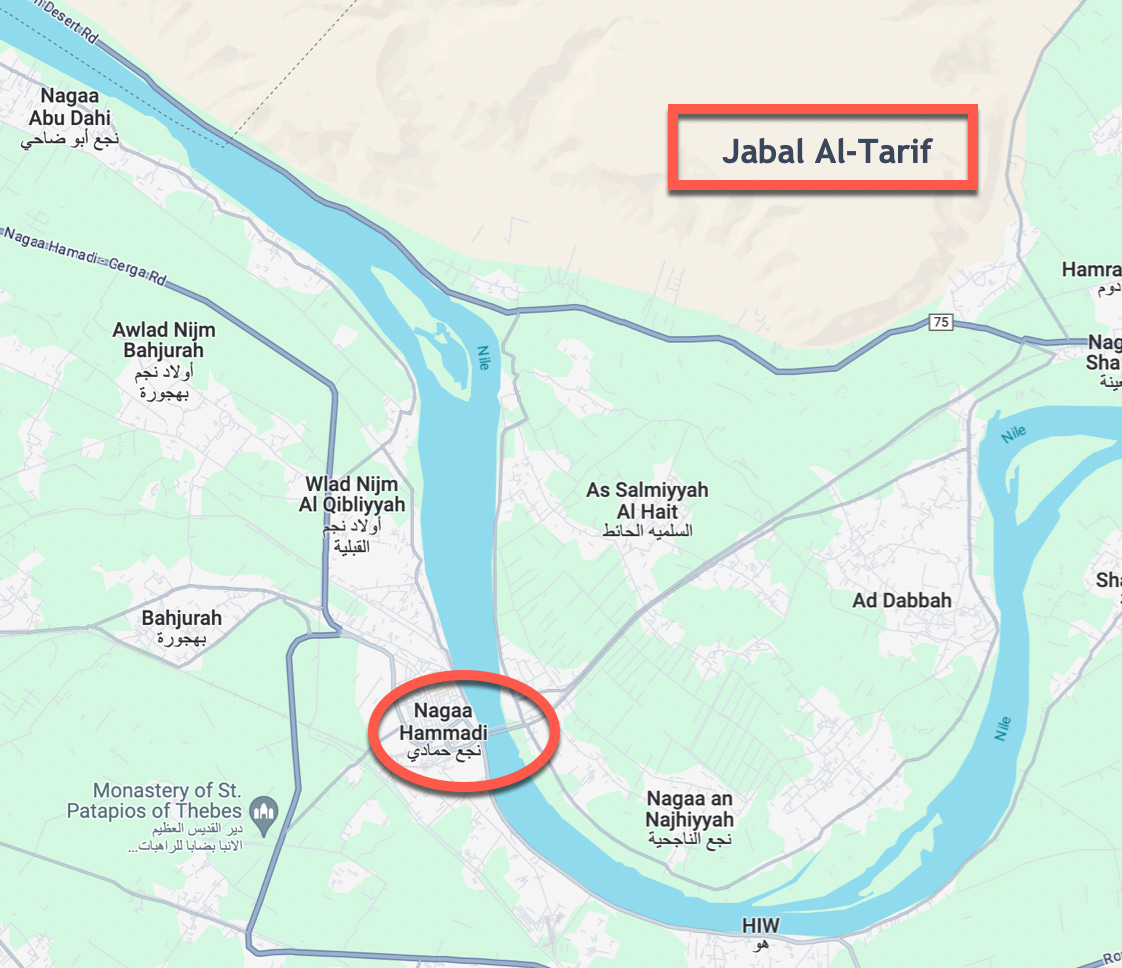

The cliffs called Jabal al-Tārif are situated less than a mile from the Nile River in Egypt. Its highest point of elevation is 1,165 feet and below, hidden for over fifteen hundred years, was a cache of secret knowledge. Incredibly, its discovery came at a time that it would be valued instead of scorned.

Image from Google Maps

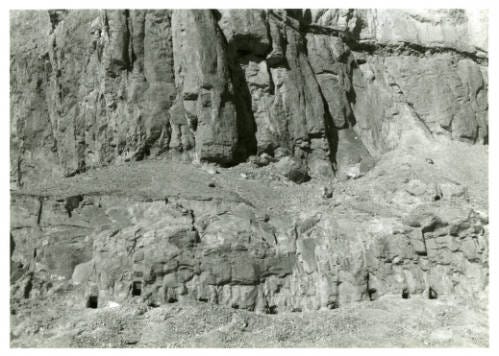

In 1945, two brothers from the hamlet of al-Qasr near Nag Hammadi walked with their camels to the base of the cliffs of Jabal al-Tārif to collect fertilizer from the talus fields that collect at the bottom. Just above the talus fields, caves run across like a row of ancient apartments. These caves have been used by the dead and the living for millenia. Elaine Pagels, in her book The Gnostic Gospels tells us that, “Originally natural, some of these caves were cut and painted and used as grave sites as early as the sixth dynasty, some 4,300 years ago.”[1]

Some caves were sacred spaces where monks meditated. These caves provide shelter for hermits, even today. It was probably a monk that secreted away a collection of books that we know today as The Nag Hammadi Library; writings from a fascinating mix of sects reflecting Gnosticism, philosophy, Judaism, and Christianity. Fortunately for us, the person who hid these around fifteen centuries ago didn’t hide them in a grave or one of the caves. It would have been robbed since all the caves sit empty now. They wanted to be sure they were safe, so they sealed them in a clay pot and buried them under the boulder deep in the talus where the farmers discovered them. When experts examined the pot, they dated it around the fourth or fifth century CE.

Image: Claremont Graduate University. Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, 1975

The caves showcase a long history of ever-changing culture and religions. James Robinson, in his Introduction to the Nag Hammadi Library, elaborates on this location, having been there himself in 1975 with a group of scholars.

“In the face of the cliff, just at the top of the talus, which can be climbed without difficulty, sixth-dynasty tombs from the reigns of Pepi I and II (2350–2200 B.C.E.) had in antiquity long since been robbed. Thus they had become cool solitary caves where a monk might well hold his spiritual retreats, as is reported of Pachomius himself, or where a hermit might have his cell. Greek prayers to Zeus Sarapis, opening lines of biblical Psalms in Coptic, and Christian crosses, all painted in red onto the walls of the caves, show that they were indeed so used. Perhaps those who cherished the Nag Hammadi library made such use of the caves, which would account for the choice of this site to bury them.[2]

As they collected fertilizer for their fields, Muhammed and Khalifah 'Ali of the al-Samman clan came upon the clay pot under the boulder, shown below. The pot was about two feet tall and was sealed with bitumen. But to the brothers, it wasn’t simply a pot. In Arabian mythology, jinns or ‘genies’ are smokeless fire-beings who sometimes dwell in inanimate objects underneath the earth.[3] There are good jinns and evil jinns. The evil ones are known to possess animals, humans, or even inanimate objects, like trees. If you harm a jinn, you could suffer from any number of diseases or might be the victim of a fatal accident, possibly attacked by a possessed animal or crushed by a tree. Understandably, Muhammed thought twice about breaking the pot, afraid that he would release a jinn and bear the consequences. The idea of finding gold inside overpowered Muhammed’s fear, and he smashed it open. Thirteen leather bound books of parchment fell out onto the talus field, and bits of yellowed parchment floated up and were caught away in the air. Five other men were with them that day, and Muhammed offered to split up the books between them, but the men thought they were worthless, so he gathered them up and brought them home to al-Qasr.

Image: Claremont Graduate University. Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, 1975

The books found in the pot are called codices, an advancement in ancient technology to replace the scroll. They were easier to carry around and you could write on both sides of the papyrus. Instead of unrolling a scroll to find a phrase, it opened like a book, so you could quickly access it.

Image: Claremont Graduate University. Institute for Antiquity and Christianity, 1975

Why were these manuscripts hidden?

Before their discovery in 1945, there were only a few sources about Gnostic teachings. Most of the references came from early church fathers from the orthodox Christian church in books and letters to their congregations warning them against these heretical doctrines. In the middle of the fourth century, the church was compiling what they considered divinely inspired manuscripts and letters into the canon of the New Testament. They rejected many known manuscripts because they didn’t deem them written ‘by the hand of God’. Some were considered harmless and informative. However, others they vehemently warned against.

Anathasius, a patriarch in Alexandria, Egypt who attended the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, wrote an Easter Letter in 367 CE to distinguish approved manuscripts from those the church fathers banned. The letter was to be read in all the monasteries in Egypt.

For truly the apocryphal books are filled with myths, and it is a vain thing to pay attention to them, because they are empty and polluted voices. For they are the beginning of discord, and strife is the goal of people who do not see what is beneficial for the church, but who desire to receive compliments from those whom they lead astray, so that, by publishing new discourses, they will be considered great people.[4]

The clay pot holding the codices could have been hidden as a reaction to Athanasius’ book banning, since they date back to the same time frame. This was a valuable collection of manuscripts, some of them hundreds of years old by that time, now officially considered heretical. The punishment for heresy, as we know from many historical accounts, could involve anything from imprisonment and torture to execution.

These were turbulent times for Christian and Gnostic sects whose teachings didn’t agree with the newly organizing Catholic church. By this time, Christians had experienced brutal waves of persecution by the Roman authorities that governed them. But after the conversion of Constantine, Christian bishops were granted certain levels of authority sanctioned by the Roman Empire. Harvey Cox explains how the bishops’ positions had changed from being heretics themselves to being accepted into the fold.

“If the liaison between church and empire was some kind of unnatural act, at least it was consensual, but a large share of the fault lies with the hierarchs of the Christian community, who had become infected with what a psychoanalyst might term ‘empire envy.’ They coveted the potency imperial officials, especially in the army, wielded over those in their charge. They calculated that by allowing themselves to be merged into the empire, maybe they could benefit from that kind of clout as well…It must have been a relief to have an emperor who—if only for his own reasons—colluded with them instead of feeding them to the lions.”[5]

The early church was organizing into a catholic, or ‘universal’ body in which followers were expected to agree on established doctrine. The watchdogs of the dogma were deacons and priests followed by the bishops at the top of the hierarchy. Pagels explains how church fathers from the second century vehemently denounced the Gnostics, writing long treatises against the so-called heretics.

“The Nag Hammadi texts, and others like them, which circulated at the beginning of the Christian era, were denounced as heresy by orthodox Christians in the middle of the second century. We have long known that many early followers of Christ were condemned by other Christians as heretics, but nearly all we knew about them came from what their opponents wrote attacking them. Bishop Irenaeus, who supervised the church in Lyons, c. 180, wrote five volumes, entitled “The Destruction and Overthrow of Falsely So-called Knowledge,” which begin with his promise to “set forth the views of those who are now teaching heresy … to show how absurd and inconsistent with the truth are their statements … I do this so that … you may urge all those with whom you are connected to avoid such an abyss of madness and of blasphemy against Christ.” [From Iranaeus, AH Praefatio[6]]

The bishops were hunting down heretics and rooting out unauthorized books. When they were found, they were burned. As you can see, a monastery near Nag Hammadi would have considered the threat this collection of heretical books would pose, considering the elevated temperature of the new force of moral authorities in the fourth century, now backed by the government and their armed forces. So, this valuable collection of books was buried not only to protect the books themselves, but the owners. It turns out that the Catholic church was very thorough in their destruction, since the only sources we’ve had until the Nag Hammadi discovery were antiheretical writings like those from Iranaeus of Lyons and Epiphanius of Salamis and a few other texts, The Secret Book of John and The Gospel of Thomas.

We’re experiencing the same frenetic book banning from the modern ‘moral authority’ now, so times haven’t changed much. Maybe we should get some clay pots of our own.

In my next post, we’ll look at the thirty-year-long saga of the Nag Hammadi collection before its translation and publication. Besides the pages used to start a fire in Muhammed’s oven, the codices were split up, sold through the black market, and smuggled into other countries.

[1]. Pagels, Elaine H. The Gnostic Gospels. 1st ed. New York: Random House, 1979.

[2]. James M. Robinson, “Introduction” in The Nag Hammadi Library in English, 4th rev. ed. (Leiden; New York: E. J. Brill, 1996), 22.

[3]. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "jinni." Encyclopedia Britannica, March 27, 2024. https://www.britannica.com/topic/jinni.

[4]. Brakke, David. “A New Fragment of Athanasius’s Thirty-Ninth Festal Letter: Heresy, Apocrypha, and the Canon.” The Harvard theological review 103, no. 1 (2010): 47–66.

[5]. Cox, Harvey. The Future of Faith. First edition. New York, NY: HarperOne, 2009, 101-102.

[6]. Pagels, Elaine. The Gnostic Gospels (Modern Library 100 Best Nonfiction Books) (pp. 7-8). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.